Address:

Robina Queensland 4226 Australia, Gold Coast, Queensland 4226

Description:

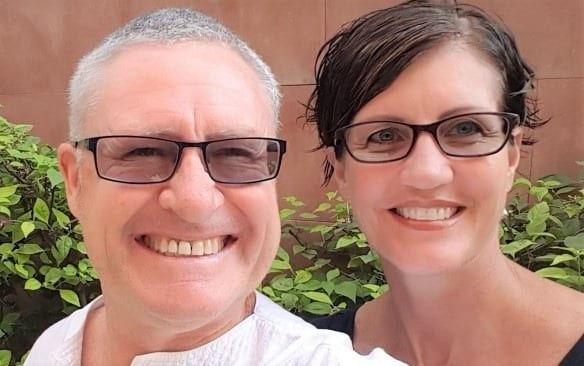

Bhutan & Beyond specialises in travel to the magical Kingdom of Bhutan, tucked away in the eastern Himalaya region between India and China. Our staff travel to Bhutan annually and have done so since 2003 making us genuine experts in this delightful destination. Plus we can assist you combine Bhutan with Nepal and India. Contact James & Nicola on enquiries@bhutan.com.au or toll free 1300 367875 then press 1.